PHOTOGRAPHS AND PUBLIC

In response to a request that they state their ideas on the problem of the photographer and his audience, Wilson Hicks, formerly an associate editor for Life, and Henry Holmes Smith, who teaches photography in the Fine Arts Department at the University of Indiana, have set down their notions. Mr. Hicks evaluates the photographer's contemporary audience. Mr. Smith lays the beginnings of a foundation by which the spectator can uread" or interpret photographs.

wilson hicks

I should like to question Walt Whitman’s dictum that to have great poets you must have great audiences, too. Whitman had a good idea, but he got it precisely backwards. Is this not the simple fact: If you have a great poet you will have a great audience or, more realistically, if you have a good poet you will have a good audience? Substituting photographer for poet, I should now like to ask, In what more effective way can the photographer improve his “audience” than by giving it better and still better pictures?

Let us examine some of the aspects of today’s photograph-viewing public:

1. That public is made up basically of snapshot lovers. A snapshot, like any photograph, is a merging of two components in register, so to say. One component is the fact, idea, or the emotion or mood, which the picture undertakes to state, present, or to describe. The other component is the graphics, or the combining of forms in light and shade into an image by which the first component is realized. The snapshot enthusiast is most frequently not concerned to any very large degree with the graphics component. To him a bad snapshot is just as important as a good snapshot because the subject matter, or fact-idea-emotion-mood component, is his primary concern. Even though little Alice’s face is chalked out by the sun or half lost in a shadow, it is still little Alice. The viewer, knowing her so well, by a trick of the imagination sees the real little Alice whenever he looks at her image, which he deludes himself into believing is much better than it actually is. The result of such mental retouching is that he is badly conditioned for looking at any photograph scaling upward in value from a snapshot.

2. That public has been fooled for years by salon photography in which, at the opposite extreme from the snapshot, by far the greater emphasis has been placed on form. Salon graphics have submerged the unique, inherent attributes of the photograph in a hybridization with the painting art, and its idea component has never been rescued from a morass of sterility and cliché. Yet the salonists, through pompous showmanship and much spoken and written mish-mash, have misled many people into thinking that their work is important.

3. That public, since the days of the stereopticon, has looked upon the camera as a toy and adopted a frivolous approach to the viewing of photographs. Three-dimensional movies, with their dependence on mechanical novelty instead of ideas, and much of television, are serving to perpetuate this state of mind. Consequently a certain handicap is put on the serious photographer.

4. That public is inundated today by a vast flood of images which, as Lewis Mumford says in his “Art and Technics” (New York: Columbia University Press, 1952), has “undermined old habits of careful evaluation and selection.” There is being waged, he reminds us, a horrific battle of man and machine from which the machine has emerged so far as the victor: witness the images mass-produced by still, movie and television cameras and mass-repeated by the printing press. I say “witness the images,” but you dare not do that. For, as Mr. Mumford says, if we tried to respond to all the mechanical stimuli which beset us we should all be nervous wrecks. Mr. Mumford asks whether being surrounded by a superabundance of images makes us more picture-minded, and answers no; we develop an “abysmal apathy” because “what we look at habitually, we overlook.” Moreover, he says, picture users, to get attention, resort to sensationalism —“make sensation seem more important than meaning”— and the shockers so prevalent today cause quieter, and better, pictures to suffer. Still further, the image producers have created a ghost-world, Mr. Mumford says, in which we lead a derivative, secondhand life in addition to our real life. This apparitional world is set and peopled with the artificial and the phoney (note many so-called news pictures). Thus in various ways are the sign and symbol of photography devaluated.

Now if the four points I have stated above are sound, and I believe they are, the photographer’s audience is poorly fitted for its job, and what a problem we have on our hands of educating or re-educating it! We can, of course, take heart from one ostensible fact: There is a segment of that audience which is as great as the greatest photography it sees. The problem really is, then, to enlarge the elite group. I say again that I know of no surer way to achieve such an end than by enhancing the quality of the camera’s product and refining the manner of its presentation.

• Consider for a moment what you are up against when you undertake to re-educate picture viewers. Above I said that a photograph is made up of two things, its graphics and its idea. Who more fruitfully than you with your photographs, provided they are of a high standard, can help large numbers of people toward a better understanding of graphics, which is to say esthetics, ill at ease though that latter term is in this brash world? Your viewers will not necessarily go to school or read expensive books to learn about the esthetics of the photograph. But you as a photographer with your images mass-repeated are also a teacher who can accomplish more than schools and books. As to the ideational aspect of the photograph, it is reacted to by the viewer with his experience, his knowledge of people and objects and the life they compose. What can you do about that? People learn about life from living it, from reading, and from looking at pictures. Here again your opportunity to enrich the experience of your viewers, except in the most limited ways, is through your photographs. What other control can you exercise or what other effect can you produce on either of these dual viewer reactions? I know of none except criticism, which I shall take up briefly later.

I suppose at this juncture I should tell you how I should go about improving the camera’s product. Though I want to be helpful, I much prefer that each photographer let his own mind play on that problem. I shall, however, go into the other matter I mentioned above, the manner of presentation of the photograph. Here my purpose is to arraign and try the wordless picture, the hunger for which (on the part of photographers) is, I feel, one of photography’s current curses. The problem regarding the audience is to induce people to understand the photograph more thoroughly, to get more out of them emotionally and intellectually, to gain more, culturally, from them. The simplest and most direct way I know to further that aim is to do some explaining of your pictures as you go along, so that eventually the audience will be more adept at “reading” them.

When you, the generic you, come upon a photograph, a bare, uncaptioned photograph which you have not seen before, your mind quickly sets about the task of translating the image into words, the silent words of mental study. You talk to yourself, telling yourself, in the verbal language to which you have been accustomed all your life, what the image means. The more articulate you are, the richer your experience directly with life and your knowledge of life outside your experience with which other graphic and word material has supplied you, the more readily and easily you can effect the conversion of the image into linguistic symbols to aid you in your understanding.

Some paintings and some photographs cause an emotional response of such clarity and power that your emotions take over completely and your intellect, which usually serves as the interpreter between the visual and the verbal mediums, is unable to act, at least on first contact between viewer and picture. In time, however, as contemplation progresses, the emotional reaction subsides and gives way to the intellectual, and the translation process goes forward. Pictures which cause an immediate paralysis of the intellect are few. Most contemporary photographs which undertake to say anything of importance bring about a mixed intellectual and emotional reaction the first time they are seen. When you look at them you are torn between “enjoyment” in the traditional sense of pondering and absorbing beauty, and rationalization. It is the nature of today’s man to approach the photograph in this way and, if it is not already equipped with a caption, to write one, as it were, himself. Of course there arc things in a photograph which neither the caption writer nor the viewer can articulate; those things constitute one of the photograph’s greatest values.

I have long admired, as applicable in his time, Aristotle’s point that reaction to a work of art is not discussible, that the only thing which matters is the individual’s own response. Ancient Greece could allow the luxury of each person’s gaining from, say, a painting, whatever his inner self pleased. It is different, now, with the photograph. The Aristotelian concept is made obsolete by the needs of our time. We may, if we like, react secretly and uniquely to a painting, a poem, or a novel, though even here, in this age of science with its relentless curiosity, whole critical cults are devoting their lives to figuring out what Picasso or Joyce or Eliot meant. But you can not be obscurantist in photography and have any larger audience than the Joycean audience.

The serious photographer who insists on saying something important either makes himself clear in his image or joins words with the image to make it more clear. Viewers see and react to pictures differently, but the photographer intends only one thing. As insistent as he is in his desire to make his point known is his viewers’ desire to understand him. Such a photographer is not content to let his audience interpret his picture according to the individual wont or whim of each member of that audience. Ele wants everybody concerned to comprehend him. To be sure, there arc some photographers who say their photographs mean something to them, therefore their purpose is achieved; if the pictures also mean something —anything —to others, well and good; if not, that is all right, too. But today’s serious viewers find disconcerting any obscurantism in the vital, modern, democratic medium of the photographic image, a medium not so elite as poetry. If you are obscure in a photograph you are put down as dull, and today’s viewers will stand for almost anything except dullness.

• I am well aware that some photographers earnestly believe that the photographic image, singly or in multiple, will someday, if not now, be a language exclusively within itself, that they will say things with the camera only and people will develop a technique for reading images without the help of the verbal-visual translation, as they have developed a technique for reading words alone. Personally I doubt it, and I have wondered about possible reasons why these photographers have the wordless pictures as a kind of flaming goal. Is it because they think of their pictures in the tradition, as great works of art which require no words to make them understood? Is it because they, being jealous, are more deeply pleased if they can do the whole job of communication (and expression!) in their own medium? Or are they doggedly determined to say what they have to say solely in pictures as a compensation for not being able to write?

There arises here the hotly controversial question whether the photograph, without words, can be universal in its meaning. We speak of universals. What do we really mean? How many paintings universal in meaning are there? The universal idea, when you stop to think about it, must perforce be extremely simple —a child nursing its mother. The Madonna is not universal because the Child is not actually nursing, a fact that is most significant to Christians, but not necessarily to nonChristians. Christians know the Madonna and can supply the title to a painting of her from previous knowledge. But can the Christian supply the title to a painting of Buddha or Hermes or Vishnu or Ra? A tree is universal, so Van Gogh did not really have to call his cypresses “Cypresses.” A Franz Hal portrait needs no title because everybody in India or Holland or Australia knows a roly-poly man with a bulbous nose and a convivial spirit. But would you be satisfied with Manet’s “Le Dejeuner sur UHerbe” if those four words did not appear underneath it? Even with them you wonder what the two clothed men and the two naked women are doing in the woods together. Are the men artists and the women models? You presume so, but you only presume. And how about Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “Sunday on the Banks of the Marne, 1939”? Is it universal?

By now I have labored my point, but to go just one step further: Is it not a fact that the painter, able through his synthesizing method to deal more often in universals, can add a few words as a title to his picture and thereby complete his statement, whereas the photographer, his picture not universal in what it says, at least not often, requires more verbal elaboration to bring it closer to universality?

• There remains the matter of criticism. The question is, where is it? Photography is without critics of consequence and any appreciable body of criticism, a criticism that grows and sets up standards for the guidance of non-photographers and photographers, a criticism that holds up the bad as well as the good so that all who look may see. This failure is an interesting and valuable study in itself. What are we going to do about it?

henry holmes smith

Fit audience fi?id, though few. —Milton

Where none admire, ’tis useless to excel. —Lyttelton

An audience comes together in mutual anticipation of an experience to be shared; in the arts it is usually assembled through the efforts of a patron-exhibitor or patron-publisher. Photography, however, that strange and bastard art, suffers a remarkable lack of both the patron and the exhibitor or publisher. A victim of its own reputation for honesty, it can find both support and audience for its facts and pseudo-facts, as when a photograph establishes the winner of a close horse race. For its expressive genius, however, its images of nature’s casual and formal richness and its special kinds of visual poetry, photography has fewer and less wealthy patrons than those who spend their substance in pursuit of old porcelain or postage stamps.

One might think to establish an audience for the mature photograph by seeking out its few and scattered patrons and banding with them to provide the methods of publication most appropriate. That aperture exists proves the merit of this thought, yet, except for aperture, the photographer stands pretty much alone as his own best patron which solves the problem with Twentieth Century efficiency and absurdity.

• In the absence of an ideal audience, with generous intelligence and purse to match, what may one expect from today’s general audience, that majority which looks at pictures in the magazines of huge circulation? If one may hope to find an audience among these, what will it be like? What shape is it now in? What may be done to generate new attitudes toward the photograph within this group?

Picture editors, working for a standard visual image that millions may relish in their haste or distraction, have fashioned a language of photography that approaches baby talk. Adult attempts to communicate with infants and small children rely mainly on verbal exclamations, interjections, meaningless repetitions, incomplete expressions and special infantile forms all of which would embarrass or disconcert both the performer and any exclusively adult audience. Much of this is found in picture journalism today. A photograph’s “impact” turns out to be the visual equivalent of the exclamation or interjection and becomes as monotonous as a bay’s cry in the night. A close look at the photograph’s “storytelling” characteristics reveals that photographs without words “tell” the general public only what is already completely familiar; this, then, resembles the meaningless repetitions of baby talk. A photograph’s “appeal” usually shows itself to be a journalistic name for the sensational, trivial, cheaply sensual or banel and morbid. “Unlettered” children neither demand nor need baby talk; adults unskilled with pictures need even less these infantile visual equivalents.

• In the absence of a publication where genuinely challenging photographs maybe frequently exhibited to the general public, one must examine other means of developing the mature from the infantile. If this problem merits attention, the only point of approach is through publishers, art directors, picture editors, managing editors, and even advertising agency art buyers. To whom do they go to school? They usually say they study with their old patron, “the general public.” We thus come full swing back to our other possibility, the education of some fragment of today’s general audience.

• The mature expressive photograph offers only casual and superficial communication for a general audience because the audience neither expects nor tries to cope with anything like the adult message that is there. This is mainly, I think, the result of bad preparation for reading photographs. No one has ever assumed that simply because we have eyes and know an alphabet, we can automatically read verbal languages. These are taught officially and formally by persons familiar with the language. Surely mere possession of the sense of sight assures no one that he will automatically become aware of the important visual relationships, structures and processes of his three-dimensional world, let alone the sophisticated echoes of these as shown in a significant photograph. That visual experience which enables one to walk safely around his home or neighborhood, and makes possible a drive along a highway is insufficient for reading and understanding the intelligently developed photographic idea. It would be profitable to test this assertion more thoroughly by confronting a group of truck gardeners and vegetable grocers with a series of Edward Weston’s peppers. Yet in such a test photography has a burden not carried even by some Twentieth Century expressionist painting. Even to a grocer a painting of a vegetable will usually lead him to “expect” something “more” than he would try to find in a photograph made with as much, or even more, thought; consequently he would try to bring to the painting a kind of “respect” which his box camera has not taught him to have for a photograph.

The above speculations lead me to believe that photographs today are at a point where words were before the dictionary standardized their appearance. In those days one might write “loke, looke” and so on for what today we write only as “look.” Today’s images, when expressing an idea by evocation through “design and symbol,” come up time after time with variations even less similar than the old spelling forms. Out of such a jumble many an observer finds it impossible to amass a “glossary” of conventionally related effects. Consequently, his “readings” at best will appear strange to him and, at worst, diffuse and weak. They appear strange because they tend to deal with the submerged and poetic experience of the individual, experiences most persons in our day prefer to face up to only in the presence of their analyst. The readings are diffuse and weak because most persons have not learned to find and use the common pool of direct experience, both intense in feeling and deep in meaning, which would best of all stabilize such poetic inferences.

• A large number of word-trained individuals who possess the interests and background to deal with mature and even poetic messages from photographs, nevertheless remain indifferent to them. This is clearly a deficiency in their schooling, a neglect that constantly becomes more difficult to excuse. It usually takes six to twelve years of practice for a native user of the language to gain the equipment with which to read works of art written with words. It may take even more experience and study to become adept at reading some of the more difficult writing in this language. Where yet is similar training for even those who are willing to become “readers of photographs”? In addition, photography lacks a coherent body of criticism. Under the circumstances, it is a minor miracle that anyone today can actually bring to focus on the expressive and poetic photograph enough knowledge and experience to read it all the way through.

• In seeking clues on a way to educate an audience, without intruding upon the provinces of the school, the general periodicals or even the customs and thinking habits of most of the public, perhaps the most profitable place to look is in one’s own experience. How does anyone close with the actualities of the photographic image and find what it may say to him?

First, he must be willing to look with attention at the image. Second, he must work patiently with and think about what he gets from the image. Third, he must be willing to turn back to the image for more help. Fourth, he must add to what he knows of this image any appropriate part of what he has previously learned from other images and directly from the world. To sum it up, he must be willing, sometimes even more willing than able. This is one way to draw appropriate inferences from complex visual implications. Today the inferences may be subtle and inconstant, for general areas of common experience and interest tend to thin out with neglect. Yet for one who is willing to work at it, the problem is difficult but rewarding. (As it is impossible to teach willingness, one may suppose there will be no reluctant scholars in this field in our time.) The major constants on which a reader may depend include:

1. The force with which image ideas are perpetuated among certain kinds of photographers and at last become conventional.

2. The fortunate fact that a photographer dealing with fundamental truths returns to the same truth more than once, using different but related material objects as his subject

3. The immense “respect” with which the great photographers regard the “natural,” the “real” and the “exact.”

4. The stability of the conventions with which human experience is accepted and evaluated in any given culture.

Certainly here are some of the components of a kind of semi-natural language, one that I doubt can be taught until it is codified. And I very much doubt that as a culture we will take the time to teach it by the direct method. Further, I do not agree that to leave out the words is always the “most direct contact between pictures and audience.” I can hardly wait to read some general principles on picture reading. I have gained much important insight from words about photographs, in aperture and elsewhere, and am not yet ready to discount intelligent words about pictures.

One of the most important steps in training part of the general audience is to help any interested person realize the rewards of staying with a difficult photograph. I think aperture could usefully publish the experience of someone who has noted the way he first responded when he saw a photograph he had not seen before, and then has compared this response with what happened when he subsequently saw the photograph a day, a week, a month and even several years later. Perhaps a small section in aperture should be devoted to methods for the detailed reading of a photograph. The possibility of applying the methods of the photo interpreters as described by Beaumont Newhall in the “Encyclopedia of Photography” (pp. 3848-55) should also be explored.

In addition, perhaps the master photographers could assemble portfolios of small bound books for children to look at. Recently a portfolio of eleven photographs of “The West” was issued by the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center and sold for about $1. Could not similar portfolios of appropriate images be issued for children? In ten years, a fiveor six-year-old may be in your audience. In five years, a ten-year-old may be there. I would also like to see issued a paper-backed book of excellent photographs that are really well printed. If this could be put on the newsstands for about a dollar, it would be worth the attempt. Perhaps some of aperture’s cuts could be so used.

In conclusion, a quotation from Randall Jarrell’s recent book “Poetry and the Age” is pertinent, if not very comforting: “Adost people know about the modern poet only that he is obscure . . . difficult. . . neglected . . . They . . . decide that he is unread because he is difficult . . . And yet it is not just modern poetry, but poetry that is today obscure ... [A survey of reading habits indicates that] 48 per cent of all Americans read, during a [recent] year, no book at all. I picture to myself that . . . nonreader . . . and I reflect “Our poems are too hard for him.” But so, too, are “Treasure Island,” “Peter Rabbit,” pornographic novels—any book whatsoever ... I call to this imaginary figure “Why don’t you read books?”—and he always answers, after looking at me steadily for a long time: ‘Huh?’ ”

Perhaps it would be wise to take John Alilton’s advice and “Fit audience find,” however few.

Mr. Smith gives an exaanple of “reading” a photograph in the following pages The photograph is reprinted on pages IS and 16.

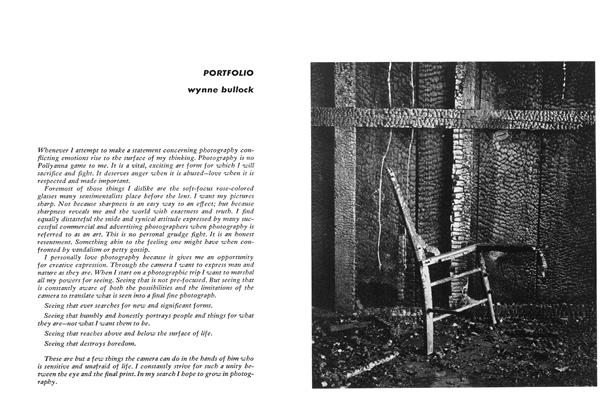

1. January 1951. Published on p. 409, American Photog.

The crudest sort of “window” seems to be cut in a dark wall upon which signs have been chalked and painted; I think of the charred side of a burnt-out truck. Framed in this window is what may be part of a human being, or a mechanized imitation of a human form. Is that metal hemisphere the tip of a knee, a head between shoulders, or the cap of a leg amputated near the knee? Is the figure alive? Why is the hose there? The bright, white arrow points not at the figure but to that haunting blackness in front of the “knee-helmeted head.” The edges of the window appear to have been cut with a torch. The substance is metal, dark iron or steel. The figure is inhuman, something captured, crushed, not living.

2. Alay, 1952. Upon the picture’s republication in aperture, No. 1, in a larger reproduction inviting closer study.

This thing may be human, but is trapped, bent, unmanned; only the thin hose darts out of the trap, but even this gesture is futile, unhopeful. The blank arrow points to the darkest, bleakest, emptiest, most cramped kind of void just in front of the nearly human form. ( An ungenerous void is possibly the least hospitable and most typical of Twentieth Century horrors: Limited oblivion! ) The opening still appears to be cut in a heavy metal wall. There is a sense of great, ominous peril for this entrapped form. The numbers provide an ambiguous set of clues, giving off toward a trinity plus one.

3. September, 1952. (At this time I learned that the photograph shows an opening in a San Francisco street, that the man is repairing a service line, and that the markings show the location of utility services under the street. This information settled, at last, a nagging but otherwise unimportant question: was the mystery and overall effect of forboding and horror stemming from my ignorance of the actual nature of the content? It was not. Even though the new information enabled me to see the prosaic form of the subject, if I chose to, the earlier effect was in no way interfered with.)

Further thought about the photograph brought the following ideas: the dark surface surrounding the opening persists in appearing to be a “wall” or vertical surface, even though my knowledge of content would make it more logical as a pavement or horizontal surface. The opening, actually a crude rectangle cut in asphalt and concrete and shown in perspective, remains a trapezoid in the vertical “wall.” The image arouses concern less for the man than for the man’s predicament, which now begins to be identified with that of everyone. A general, almost abstract, apprehensive feeling is noted. There are overtones of darkness, night, gloom, doom. The man becomes a “black knight” of night, with none of the usual knightly prerogatives. His steed is an underground pipe, his weapon perhaps a small, intense flame; his task and general posture belittle his human functions.

He masks his face with metal; his place of employment is a minute, near-gate to the underworld that is all mankind’s potential lot. In a day when a lead mine may be the safest spot on earth for human kind, this tiny opening in a San Francisco street becomes a part that stands for the whole, rhetorically speaking a synecdochic “figure.”

Thus prepared, head bent, the human character of our features obliterated by a metal shield, our shoulders cramped, our burden oppressive, our goal obscure but certainly horrid, we may undertake our downward voyage. There is the reminder that the nether world is no darker than the place from which we leave: the fragment of the upper world that frames the pit is just as black as the pit itself, a void-containing void.

(At this point in the reading, attention was turned to possible sources of the photographer’s power to evoke the state of apprehension, the sense of being haunted by a weird metamorphosis of the familiar. The following notes, all taken during direct consideration of the photograph, are the basis for the continuation of this reading:)

Grave slab laid aside fetal burial

Helmeted warrior

His weapon the bright arrow

Triangle ambiguity—partial statement mystery of our time

Square our kind of “mystery”

The burial (ritual burial) Man in cab of truck—dead

Here, then, for one observer is a final disclosure of the photograph’s source of power. A “visual pun” calls to mind the pit burials of ancient times in which the corpse’s legs and arms were drawn into the posture of the unborn human being. The man’s body, even though seen only in part, suggests this explicitly. With this is connected the “infantile” sacrificial “deaths” on today’s highways from speed, reckless behavior, drunkenness and so on. In a strange and most appropriate way we are being given an archeologist’s glimpse of ourselves. That is enough almost to give anyone a shudder, especially when the view is presented with the tonality and structure of this image. To pursue the “warrior-helmet” theme for a moment, there is a suggestion that this helmeted warriorhero has entered his “grave” of his own volition. The only visible weapon is the white painted arrow, which is actually directed at the blackness of the pit. This “magic” weapon floats above him, his courage or his “duty.”

This line of thought leads toward evidence that further suggests and supports the suicide theme: the persistent idea of the automobile truck cab, charred or burnt-out, the hoses running into the “compartment” where the “body” lies slumped, the overwhelming sense of a willed accident. This tightens up another “hunch” about the “unmanned” aspect of the image or the image as a tragic figure with its general atmosphere of immolation. The man’s posture resembles that of an automobile accident victim trapped in the car’s front seat.

In conclusion we can call attention to the fact that by returning to a photograph on appropriate occasions to reconsider its possible meanings, one may often gain insight into the several directions in which a group of meanings may move, at the same time remaining within the limits of a given emotional effect.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue