CLARENCE JOHN LAUGHLIN

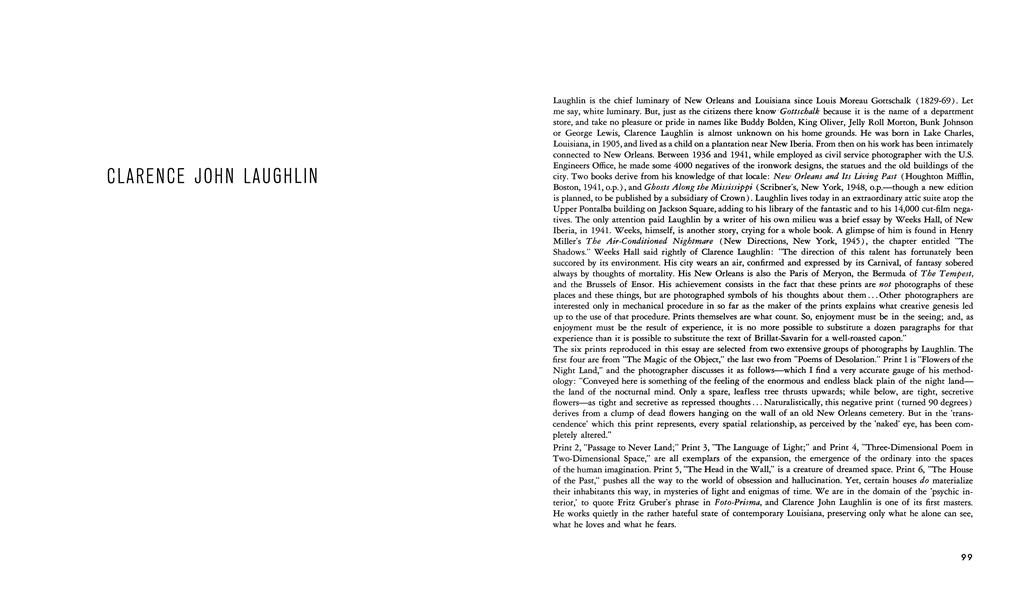

Laughlin is the chief luminary of New Orleans and Louisiana since Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-69). Let me say, white luminary. But, just as the citizens there know Gottschalk because it is the name of a department store, and take no pleasure or pride in names like Buddy Bolden, King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, Bunk Johnson or George Lewis, Clarence Laughlin is almost unknown on his home grounds. He was born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, in 1905, and lived as a child on a plantation near New Iberia. From then on his work has been intimately connected to New Orleans. Between 1936 and 1941, while employed as civil service photographer with the U.S. Engineers Office, he made some 4000 negatives of the ironwork designs, the statues and the old buildings of the city. Two books derive from his knowledge of that locale: New Orleans and Its Living Past (Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1941, o.p.), and Ghosts Along the Mississippi (Scribner’s, New York, 1948, o.p.—though a new edition is planned, to be published by a subsidiary of Crown ). Laughlin lives today in an extraordinary attic suite atop the Upper Pontalba building on Jackson Square, adding to his library of the fantastic and to his 14,000 cut-film negatives. The only attention paid Laughlin by a writer of his own milieu was a brief essay by Weeks Hall, of New Iberia, in 1941. Weeks, himself, is another story, crying for a whole book. A glimpse of him is found in Henry Miller’s The Air-Conditioned Nightmare (New Directions, New York, 1945), the chapter entitled "The Shadows.” Weeks Hall said rightly of Clarence Laughlin: "The direction of this talent has fortunately been succored by its environment. His city wears an air, confirmed and expressed by its Carnival, of fantasy sobered always by thoughts of mortality. His New Orleans is also the Paris of Meryon, the Bermuda of The Tempest, and the Brussels of Ensor. His achievement consists in the fact that these prints are not photographs of these places and these things, but are photographed symbols of his thoughts about them... Other photographers are interested only in mechanical procedure in so far as the maker of the prints explains what creative genesis led up to the use of that procedure. Prints themselves are what count. So, enjoyment must be in the seeing; and, as enjoyment must be the result of experience, it is no more possible to substitute a dozen paragraphs for that experience than it is possible to substitute the text of Brillat-Savarin for a well-roasted capon.”

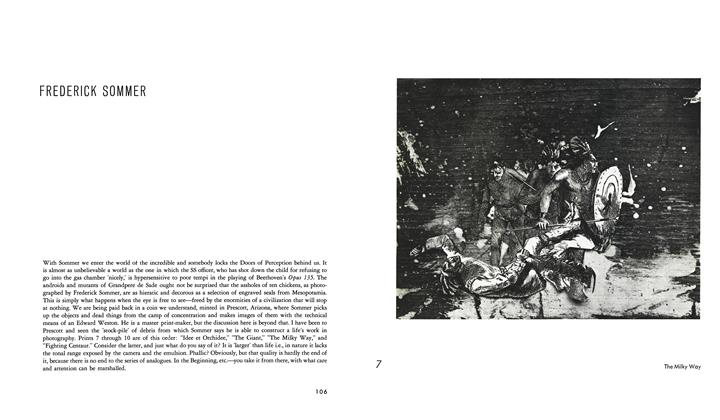

The six prints reproduced in this essay are selected from two extensive groups of photographs by Laughlin. The first four are from "The Magic of the Object,” the last two from "Poems of Desolation.” Print 1 is "Flowers of the Night Land,” and the photographer discusses it as follows—which I find a very accurate gauge of his methodology: "Conveyed here is something of the feeling of the enormous and endless black plain of the night land— the land of the nocturnal mind. Only a spare, leafless tree thrusts upwards; while below, are tight, secretive flowers—as tight and secretive as repressed thoughts ... Naturalistically, this negative print (turned 90 degrees) derives from a clump of dead flowers hanging on the wall of an old New Orleans cemetery. But in the 'transcendence’ which this print represents, every spatial relationship, as perceived by the naked’ eye, has been completely altered.”

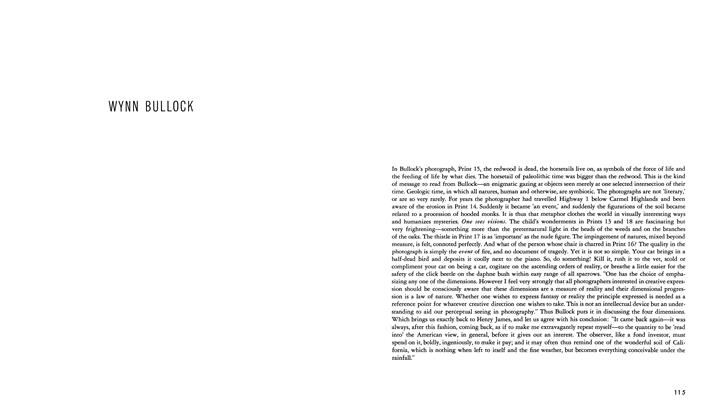

Print 2, "Passage to Never Land;” Print 3, "The Language of Light;” and Print 4, "Three-Dimensional Poem in Two-Dimensional Space,” are all exemplars of the expansion, the emergence of the ordinary into the spaces of the human imagination. Print 5, "The Head in the Wall,” is a creature of dreamed space. Print 6, "The House of the Past,” pushes all the way to the world of obsession and hallucination. Yet, certain houses do materialize their inhabitants this way, in mysteries of light and enigmas of time. We are in the domain of the 'psychic interior,’ to quote Fritz Gruber’s phrase in Foto-Prisma, and Clarence John Laughlin is one of its first masters. He works quietly in the rather hateful state of contemporary Louisiana, preserving only what he alone can see, what he loves and what he fears.