ROBERT BERGMAN: PORTRAITS, 1986-1995

REVIEWS

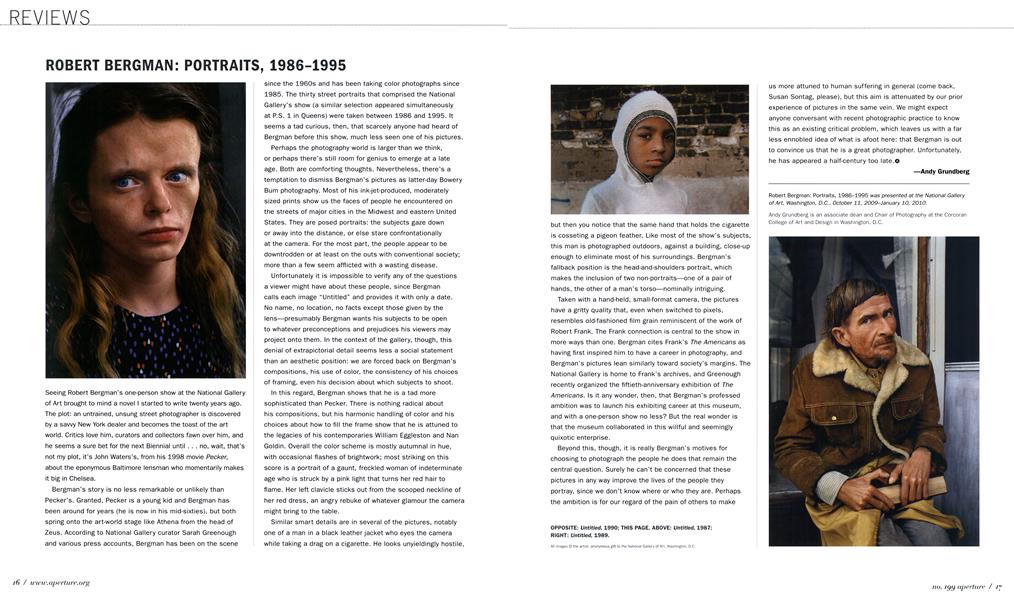

Seeing Robert Bergman's one-person show at the National Gallery of Art brought to mind a novel I started to write twenty years ago. The plot: an untrained, unsung street photographer is discovered by a savvy New York dealer and becomes the toast of the art world. Critics love him, curators and collectors fawn over him, and he seems a sure bet for the next Biennial until ... no, wait, that’s not my plot, it’s John Waters’s, from his 1998 movie Pecker, about the eponymous Baltimore lensman who momentarily makes it big in Chelsea.

Bergman’s story is no less remarkable or unlikely than Pecker’s. Granted, Pecker is a young kid and Bergman has been around for years (he is now in his mid-sixties), but both spring onto the art-world stage like Athena from the head of Zeus. According to National Gallery curator Sarah Greenough and various press accounts, Bergman has been on the scene

since the 1960s and has been taking color photographs since 1985. The thirty street portraits that comprised the National Gallery’s show (a similar selection appeared simultaneously at P.S. 1 in Queens) were taken between 1986 and 1995. It seems a tad curious, then, that scarcely anyone had heard of Bergman before this show, much less seen one of his pictures.

Perhaps the photography world is larger than we think, or perhaps there’s still room for genius to emerge at a late age. Both are comforting thoughts. Nevertheless, there’s a temptation to dismiss Bergman’s pictures as latter-day Bowery Bum photography. Most of his ink-jet-produced, moderately sized prints show us the faces of people he encountered on the streets of major cities in the Midwest and eastern United States. They are posed portraits: the subjects gaze down or away into the distance, or else stare confrontationally at the camera. For the most part, the people appear to be downtrodden or at least on the outs with conventional society; more than a few seem afflicted with a wasting disease.

Unfortunately it is impossible to verify any of the questions a viewer might have about these people, since Bergman calls each image “Untitled” and provides it with only a date.

No name, no location, no facts except those given by the lens—presumably Bergman wants his subjects to be open to whatever preconceptions and prejudices his viewers may project onto them. In the context of the gallery, though, this denial of extrapictorial detail seems less a social statement than an aesthetic position: we are forced back on Bergman’s compositions, his use of color, the consistency of his choices of framing, even his decision about which subjects to shoot.

In this regard, Bergman shows that he is a tad more sophisticated than Pecker. There is nothing radical about his compositions, but his harmonic handling of color and his choices about how to fill the frame show that he is attuned to the legacies of his contemporaries William Eggleston and Nan Goldin. Overall the color scheme is mostly autumnal in hue, with occasional flashes of brightwork; most striking on this score is a portrait of a gaunt, freckled woman of indeterminate age who is struck by a pink light that turns her red hair to flame. Fier left clavicle sticks out from the scooped neckline of her red dress, an angry rebuke of whatever glamour the camera might bring to the table.

Similar smart details are in several of the pictures, notably one of a man in a black leather jacket who eyes the camera while taking a drag on a cigarette. Fie looks unyieldingly hostile, but then you notice that the same hand that holds the cigarette is cosseting a pigeon feather. Like most of the show’s subjects, this man is photographed outdoors, against a building, close-up enough to eliminate most of his surroundings. Bergman’s fallback position is the head-and-shoulders portrait, which makes the inclusion of two non-portraits—one of a pair of hands, the other of a man’s torso—nominally intriguing.

Taken with a hand-held, small-format camera, the pictures have a gritty quality that, even when switched to pixels, resembles old-fashioned film grain reminiscent of the work of Robert Frank. The Frank connection is central to the show in more ways than one. Bergman cites Frank’s The Americans as having first inspired him to have a career in photography, and Bergman’s pictures lean similarly toward society’s margins. The National Gallery is home to Frank’s archives, and Greenough recently organized the fiftieth-anniversary exhibition of The Americans. Is it any wonder, then, that Bergman’s professed ambition was to launch his exhibiting career at this museum, and with a one-person show no less? But the real wonder is that the museum collaborated in this willful and seemingly quixotic enterprise.

Beyond this, though, it is really Bergman’s motives for choosing to photograph the people he does that remain the central question. Surely he can’t be concerned that these pictures in any way improve the lives of the people they portray, since we don’t know where or who they are. Perhaps the ambition is for our regard of the pain of others to make

us more attuned to human suffering in general (come back, Susan Sontag, please), but this aim is attenuated by our prior experience of pictures in the same vein. We might expect anyone conversant with recent photographic practice to know this as an existing critical problem, which leaves us with a far less ennobled idea of what is afoot here: that Bergman is out to convince us that he is a great photographer. Unfortunately, he has appeared a half-century too late.©

—Andy Grundberg

Robert Bergman: Portraits, 1986-1995 was presented at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., October 11, 2009-January 10, 2010.

Andy Grundberg is an associate dean and Chair of Photography at the Corcoran College of Art and Design in Washington, D.C.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

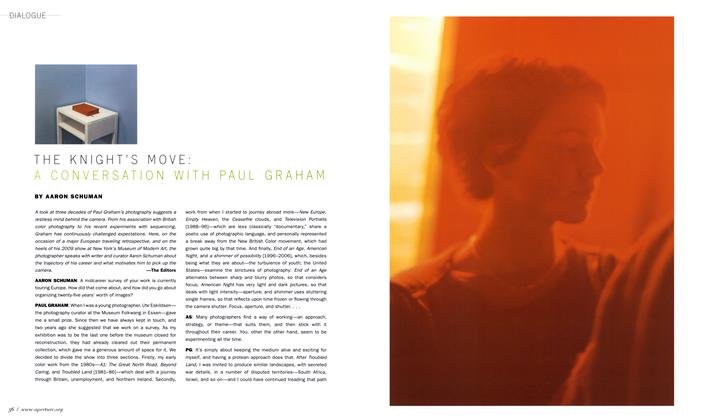

DialogueThe Knight's Move: A Conversation With Paul Graham

Summer 2010 By Aaron Schuman -

Portfolio

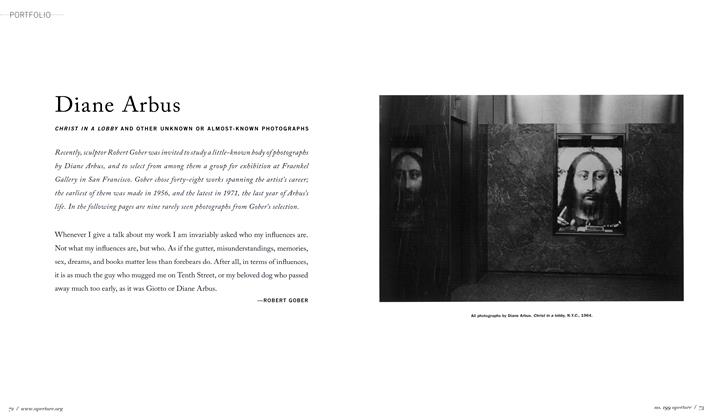

PortfolioDiane Arbus: Christ In A Lobby And Other Unknown Or Almost-Known Photographs

Summer 2010 By Robert Gober -

Mixing The Media

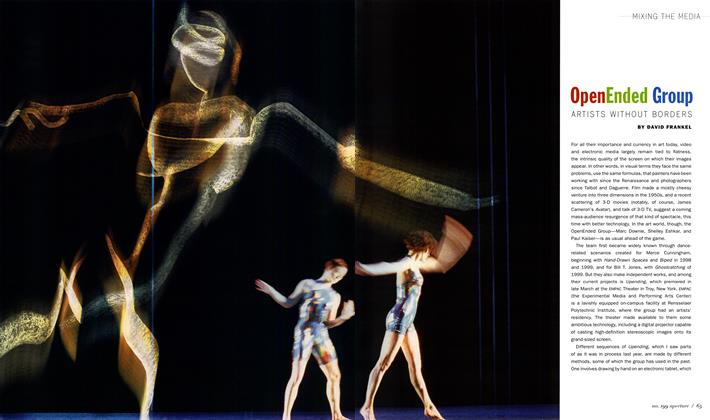

Mixing The MediaOpen Ended Group: Artists Without Borders

Summer 2010 By David Frankel -

Theme And Variations

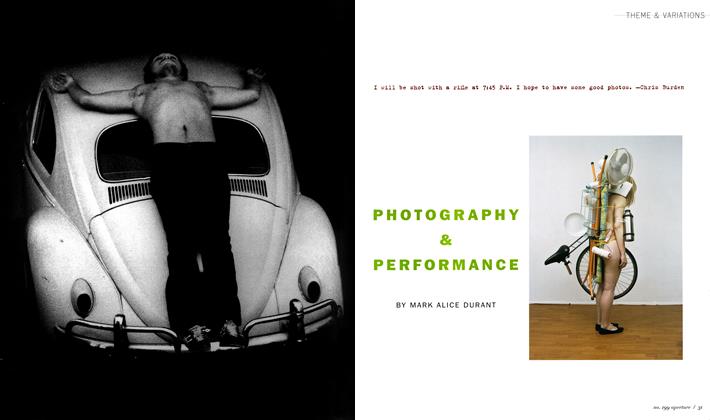

Theme And VariationsPhotography & Performance

Summer 2010 By Mark Alice Durant -

On Location

On LocationPiemonte: Koudelka

Summer 2010 -

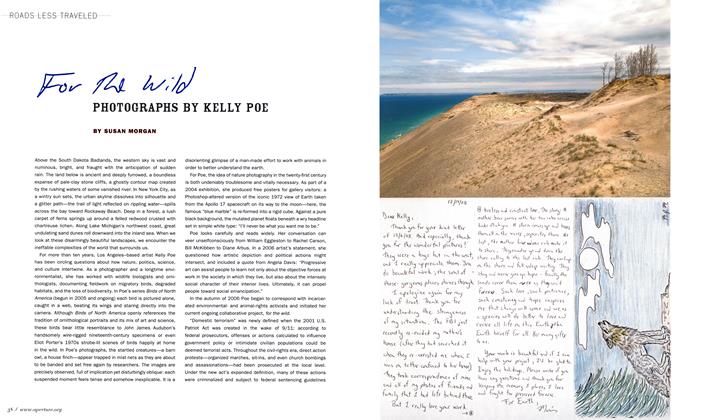

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledFor The Wild: Photographs By Kelly Poe

Summer 2010 By Susan Morgan

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Andy Grundberg

Reviews

-

Reviews

ReviewsMomentum 4: Roe Ethridge/county Line

Winter 2005 By Ann Wilson Lloyd -

Reviews

ReviewsJoe Deal: New Work

Summer 2010 By Brian Sholis -

Reviews

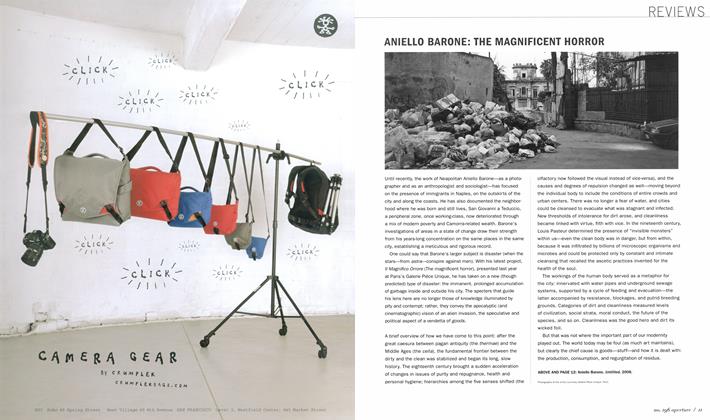

ReviewsAniello Barone: The Magnificent Horror

Fall 2009 By Giuseppe Merlino -

Reviews

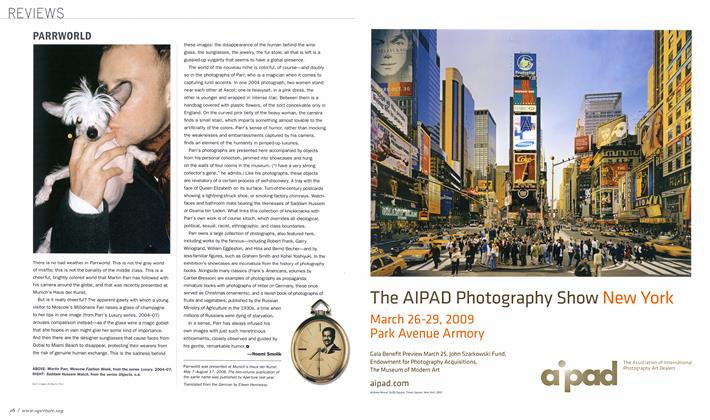

ReviewsParrworld

Spring 2009 By Noemi Smolik -

Reviews

ReviewsPainting On Photography: Photography On Painting

Spring 2006 By Polly Ullrich -

Reviews

ReviewsThree Shows On Time And Movement

Spring 2007 By Shelley Rice